🪟 Transcript 42 - Death and self-realisation

Transcript #42 (Part 5): On the awakening of the spirit through the crisis of death and mortality.

Table of contents

PART 1: NATURE

PART 2: COURT OF JUSTICE

PART 3: HOUSE OF MIRRORS

PART 4: EXISTENTIAL LETTERS

PART 5: IDEALS

Death and self-realisation

🪟 42 - Death and self-realisation

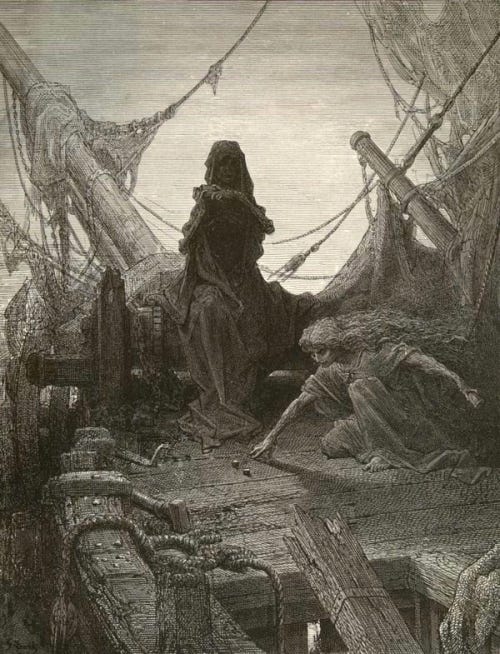

There is a certain ghostliness to everyone, visible when you people-watch with the thought that every face you see is like faces in a dream, on the verge of blurring and fading away. None of us are all that far from death, in truth. Even the most vibrant and youthful of faces are not far from paling away. It is all too visible! In silence, that is, it is all too visible—not when one is caught up in the dilly-dally of mindless sensuousness. In silence, one sees; one sees that an angel of death goes before each one of us, slowly and surely, leaving traces on the paths we tread; one sees that she carries with her a lantern of the dark, threatening us, and ultimately, enlightening us to our meagreness. Who is secure from the inconspicuous hand of death? Any act I perform, in this moment or the next, may be my last. Any possibility I choose to fulfil in the present moment may lead into countless possibilities severed into the oblivion of unrealisation. Death comes of her own accord; indeed, she comes at her own time, like a thief in the night, and just like a thief in the night, it is never so “far away that it is not to worry about”—the way we speak about black holes, except death is rather more like a black hole from the inside, it is an activity within us that conspires against us, like a ticking time bomb that is not so much constant but exists in a cycle of realising and forgetting itself. But while we may forget the taint of death, it does not forget us. As such it looms over life itself.

Yet, within each of us, there is an infinite difference. The angel of death goes before us not as a collective, not as a unit. Within each of us, there exists a death-relationship, a relationship which is equal to all, and yet all the same, fully unique to all. As life itself is, for an individual, absolute in its unfolding, so death too operates with the same individual-centricity. Certainly!—in one’s death-relationship, just like in all human and psychical relationships, there are patterns that repeat themselves over and over again consistently, over generations and epochs. Children, seeing infinite possibility ahead of them, are ignorant of death. The overachievers suppress it with their own over-achievement, with striving, with “the grind”. Many are in some measure afraid of it, and prefer not to think too much about it, sweeping it under the carpet with the help of a comforting cliché such as “ignorance is bliss”. Religious fundamentalists, on the other hand, sublimate death as a passing over into an afterlife, like the passing of a trial examination through to St. Peter’s pearly white gates. (Many, however, do this rather unseriously, as if death was something trivial, which is to me one fault of Christendom—the popularisation of Christianity to the point of it becoming about communal affirmations rather than building true religiosity, which properly and deeply constitutes the death-relationship).

Some others treat it with more seriousness, employing a philosophy of defence against the threat of death—stoics find serenity by way of narrating oneself into indifference, or so they say, as Epicurus says, “when we exist, death is not, and when death exists, we do not”. Simple as that! (Or is it really… simple as that?) Buddhists transcend death in a somewhat similar, albeit more mystical way. Some others, usually younger ones, read Camus and Nietzsche a couple of times, and seeing themselves in a boxing ring against death, call themselves “absurdists” or “ubermenschen”, imagine themselves unwilling to resign, wanting to lose nobly or heroically. And so on and on. There are patterns to the death-relationship, to be sure. In order to bear a life where death is always possible, there are cultural and systematic patterns of narration: there are solutions to the problem of death’s thieving, whether they are eternally-affirmed or mere psychological sleights of hand that we employ in order to either defend ourselves or play offensively against the fact of our own impending evaporation. Each strategy stands to be tested for its merits, to be sure. But, either way, it remains that one has to reckon with this threat—in one way or another. And within cultures and systems, there are common attitudes. One may neutralise it with by symbolically turning his head away in avoidance, another with symbolically turning his nose up in defiance, another may aestheticise it from a distance, another may face every other direction in order to avoid gazing at it directly (which, like when one turns his back to sunlight, he will only end up looking at its shadows), while another might be renouncing death by renouncing himself away—either way, one remains in an indefinite tussle with it. Otherwise, the last option is to take complete offence at life, or to give in to weariness; to act with finality on this tussle, the only option here being to commit suicide; where, equipped with the tools of living, one employs it in one giant halt of a crescendo to severe life of itself. Why else is death a most inexhaustible discourse, and why else is there never a final opinion on death? In this manner, death is always moving, a primordial spirit of its own.

Indeed, what remains is that as humans, we are to be subjected to a death-relationship at all! It is not a matter of choice that death is the constant thread. It occurs and recurs among humans alike as a matter of life’s due unfolding, where life itself is incomplete and self-divided. In one way, while we wield the absolute power of choice at the present moment, and we can choose one way or another, which way to turn, left or right, how slow or fast to go, but in another way, looking retrospectively and prospectively, it is as if life has already been decided for us! It is has been decided by virtue of life being how it is; life is life, life is what it is, and life is incomplete and self-divided. How can the multitude of differences among individuals possibly trump or be in disregard of the very nature of life that compels those differences in the first place? All humans are different, in one sense; but all humans are also the same. Both are true at once. Yet, within each of us, as it is for you and me, there still indeed exists an infinite difference. I am all of us at once, but primarily I am me. When one goes before death, when the death-relationship takes the podium, it is all too clear—it is the individual who takes primacy! The human race might be made up of a community of dreamers who dream the dream of death, this is true, but it is above all the single individual who dreams—life is solipsistic, the ‘dream’ may be shared by all, but the dreamer participates in the ‘dream’ as the dreamer first of all. It is only in systematic theory, such as in psychoanalysis, that the dreamer interacts with the ‘dream’ as a community, as many persons. This may be true in retrospect, but the multitude in me nevertheless stands to be me. The problem of death, even if mechanistically understood, universally spoken of, and profoundly hinted to in the epoch’s works of art, remains to be dreamed at the absolute nexus—the point of subjective experience. The individual alights to the death-relationship in this way, in the sharing of a common experience which cannot be shared.

Consequently, in this realm (of individual experience), as is applicable to each of us, there is a common development in the unfolding of life wherein the death-relationship enters the fray. There comes a certain period called a ‘crisis’. It may be a period of emotional decline, supplanted by loss and grief over the death of a loved one, by overwhelming hurt and disappointment, even by boredom and persisting unfulfillment; it may be by the realisation of the futility of “trying”, by the dark and harrowing of evil or emptiness of the world, by a personal confrontation with death, by the terror of the unspeakable void. For the masculine, I have observed this crisis all too frequently to be some close call with death, whereas for the feminine, those gifted beings who are more in tune with the invisible air, something so physically extreme is usually less prerequisite (how remarkable that this is the case—but I digress!). In one way or another, death enters the fray via the development of a crisis, ushering one into his or her death-relationship. And however it comes, one tends to awaken to it catastrophically—for the true realisation of death does not begin at birth, very rarely in childhood and youth, and when it does happen it is never sits peacefully, for the fact of death is an never easy one for one to accept, though it may be emotionally dealt with it in this or that way—it alights with the quality of horror, as a phantasmagoria—it is never fully settled emotionally, never fully integrated spiritually, and sometimes even fully unacceptable propositionally, yet it persists unconsciously, muddled up with the very concept of life (in conception and in action).

From the eternal point of view, this crisis over one’s death-relationship is a necessity. It happens, it tends to happen, and it is right for it to happen. Is this the morbid fact of life? Life unfolds into that which leads each one to say (authentically)—”life is suffering”, “life is madness”, “life is pointless”, “life is meaningless”—and yet the crisis is right to happen. Life is suffering when it is permeated with its own opposite, but, here is what happens thereafter. It is out of this crucial moment of awakening to one’s own self-division that the spirit emerges. OK. Now, what is this spirit that emerges? To answer this question, let me begin: what is the individual before and after this emergence of spirit? Let me begin with the individual prior to this emergence of spirit. Few images portray this better than that of a group of overgrown teenagers, brutish persons living ‘without a care in the world’, as though they commanded an endlessness of time ahead of them. The attitude is one of treating time as trivial, paying heed only to the amusements of the momentary, as if life was a buffet with a time limit one thought was too far off to consider, only to be brought into the rude awakening of being told he has no more than five minutes left! They persist in a state of shallowness, conforming not to the truth of death which lurks in silence and in dread, instead they conform to the whimsical norms and distractions that keep them from truly facing their mortality. They are like butterflies who flutter for a day and think it is forever.

But, ah—here I despair over my sense that today this is how most of us are! With the modern arsenal of amusements, so well-equipped that our attention is a demand brimming with limitless supply, the crisis tends to be delayed, and sometimes it is persistently delayed as long as our attention is kept imprisoned by the machine that sustains it—the technocapitalist machine; the seductive “hand of the market”, effective by its hiddenness and hidden by its effectiveness; new inconspicuous (or, conspicuously inconspicuous) godheads of our time. How rare it is for one to well and truly awaken to spirit! These days it is not “delayed gratification” that is the problem, it is delayed silence which is the problem. You see this when you walk in most public spaces. It is no longer quiet, they pipe music through—from one store to another, music passes; the world is encapsulated in the brief moment of amusement after amusement, from one to another, to achieve silence even for more than a minute is laudable these days. What grave impoverishment, that we should live most of our lives (and sometimes all our lives) as half-lives! In these times, silence is not only unbearable, as it is with a perpetually-distractible infant, one is, what more, addicted to non-silence. The modern individual is addicted to not only particular distractions, but to the very element of the distraction, that which puts silence off for another minute, another hour, another day (no matter what it is). Nevertheless there is hope. I believe and have hope in the self—for I have seen a plentitude of evidence in the universal becoming of the self! For when no one takes us through our rite of passage, and when the world around us conspires to put silence off for another day or year, the self figures out how to initiate itself. It does so with the arousal of suspicion, and of doubt—the self, by virtue of the unconscious, becomes suspect of itself and the appearance it is grounded upon. For it is not the manifold sounds of the world which is deafening but silence which is truly deafening. When silence is drowned out, the ring of death’s silence inevitably cuts through; it rings more loudly than the loudest horns, and yet it is quieter than softest stroke of a brush.

Now, what is the individual upon and after this emergence of spirit? But first of all, what can it possibly mean—that one’s spirit should emerge, with the help of silence, and with the help of the initiation of the self? A man with spirit, broken down before the calamity of his finitude, is restored in view of his infinitude (his origin and his destination)—which bursts open and emancipates all of time from the paperweight that is the sensuous meandering of the present moment—returning him to his eternal origin, aeterno modo [the mode of eternity], the timeless ground of excess nothingness, the womb from which he was given life and to which he is to return to. And what is the real indication of “spirit” here, other than the finite subject imbued with a profound earnestness, an earnestness that is grounded authentically and deeply in the source code of being itself, which is infinite and eternal? Babies are birthed into matter, into being, but they are not yet awakened to their spirit. Although babies are still born as a spirit from the moment of birth, they only become fully themselves later in life—as adults, in the crucial moment of “maturity” that follows a crisis (and it follows that prior to this moment, one must have lived for a certain time within sensuous-psychic categories). After all, is it not already a cliché that crisis leads to maturity, especially where (this is not usually spoken of) the crisis is so painful that it cannot be averted with the defensive equipment previously relied upon, which, in the case of death, one’s defensive equipment, being based in time, was so superseded that he had to come to see beyond time and out of time? In this way, as they say, crisis leads to maturity; out of its transformation springs a new viewpoint, and it is the grounding element. A tree becomes interested in its roots; a human being comes vividly before his own nothingness and somethingness: that dialectic that constitutes him.

At last—how all of this rings with such obtusity, such arrogance, the sound of one thinking his opinion to be all too acute and certain! Ah… if all of this is to be ripped apart and thrown away, if I am too be cussed and dismissed for my certainty, for my use of archaic terms, for my ‘medieval’ thinking, I am fine with it, but there is only one thing I would urge, which I shall insist upon with all my strength. It is this. In life we can choose whichever way we want (pragmatically speaking), but death is the sword of time, and insofar as we are made of time, death shakes us into submission. How so? In looking at life in the eye, something achievable only in silence, something painful happens as the unwholeness of reality gazes back. But it is from this unwholeness, from the cliff of life, that the grounding questions of being are opened. The eternal is awakened—as the mysterious, elusive, and yet infinitely captivating language of wholeness and unwholeness. To me, this is is true meaning of the notion: “no man can ever be secure until he has been forsaken by Fortune”. This notion tends to be about an immediate desire, about wanting something, someone, a woman perhaps, and not getting it. The short circuitry of desire points to an endlessness of desire and the suffering that follows it. Yes. But it is only when one comes before death—when life itself short circuits, that one comes before both life and death, wherein the endlessness of desire also comes before life and death—it is then that the eternal is ripe, and speaks personally to transform it! Yes—in this way, coming into being is not brought about by a good education, not by being parented exceptionally, not even by the charity of a lover (though it is certainly helped by such things); it is brought about first and foremost by an authentic1 destruction—by the first confrontation of life’s negation, that which threatens to dissipate the body and mind into entropy; by the discovery of the fundamental lack that exists in the short circuitry not only of desire but of life itself; as the psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein says in her 1912 paper, one’s coming into being is an emergence brought about by destruction, by dying inwardly—by fully assuming death in living.

Life is a dream, but then death is a dream within a dream; but this dream within a dream, though it negates life, is simultaneously that which compounds and exponentiates it—for it gives birth to the spirit, the eternal purposefulness and the true earnestness in the individual. It is this emergent spirit that admits, authentically, removed from the technocapitalist world and incessant non-silence, permeated with an eternal awareness, what Kierkegaard penned in his well-known journal entry over two hundred years ago: “the thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live and die. That is what I now recognise as the most important thing”. Only from this point of view of being aeterno modo, can one become infinitely earnest about his or her life—while knowing that it shall end, while essentially being self-divided. This is the truth held within the death-relationship, which cannot be faked or coerced into being, wherefrom one begins to truly understand the truth of mortality or finitude—which then propels him or her towards life, and “life to the fullest”. For it is death that compels us fully into life—it is death that is life’s supreme testimony—in the same way it is despair that compels us to joy, anxiety that compels us to peace, pain that compels us to comfort. And death is infinitely higher (or lower, since it is in opposition), insofar as life itself is higher than joy, peace, or comfort (symbolically speaking), so too death is infinitely greater than these. It is through the morbid road, by essentially becoming a ‘living dead’, that one comes fully and newly into life—returning to the world like a renewed being, like a child reborn in a second birth. In other words, one finds life—true life—only by going through death.

This moment has to be marked with authenticity. The spirit will not be born from an arms-length trifling with death, which sees and feels death out of amusement, or pokes at it in a passing manner. It will be born from an authentic crisis, from a jolt that leads to a hyperactivity over death (the hyperactivity being the indication of authenticity).